Elizabeth C. Reilly

The early Hindu astrologers used a magnet—an iron fish compass that floated in a vessel of oil and pointed to the North. The Sanskrit word for the mariner's compass is Maccha Yantra, or fish machine. It provides direction, and, metaphorically, illumination and enlightenment. These essays began in 2006 in India. Since then, my work has expanded to Mexico, China, the European Union, and Afghanistan. Join me on a journey throughout this flat world, where Maccha Yantra will help guide our path.

About Me

- Name: Elizabeth Reilly

- Location: Malibu, California, United States

Sunday, November 11, 2012

Saturday, July 10, 2010

Sun-Kissed Summer Bounty

Hundreds of them have the blush of the sun’s kiss. For two years, I have missed apricots on my little tree, but this year it produced a bumper crop. My father says apricots can be a temperamental fruit to grow, and he has seen trees do the very same thing as mine: produce wildly and then take a break. I thought perhaps the lack of apricots was due to The Great Bee Death, about which I had been hearing so much. Although Malibu is not exactly the optimum place for stone fruit since we have so little heat and an abundance of fog, I have waited patiently for them to ripen, chasing off robins and blackbirds daily who were looking for a sweet treat.

Hundreds of them have the blush of the sun’s kiss. For two years, I have missed apricots on my little tree, but this year it produced a bumper crop. My father says apricots can be a temperamental fruit to grow, and he has seen trees do the very same thing as mine: produce wildly and then take a break. I thought perhaps the lack of apricots was due to The Great Bee Death, about which I had been hearing so much. Although Malibu is not exactly the optimum place for stone fruit since we have so little heat and an abundance of fog, I have waited patiently for them to ripen, chasing off robins and blackbirds daily who were looking for a sweet treat.This evening marked the first picking of the crop, which was a bit of a precarious task since various cacti grace the base of the tree. I enlisted my youngest son, Kevin, to join me, and the result was a glorious array of sun-burnished, pale orange fruits. We tried several and declared them perfect.

Caitlin, my youngest, who is enjoying the French countryside this week, is having the opportunity to try many a mouth-watering dessert, but she knows her mother is no slouch when it comes to sweets, and in particular, when it comes to French sweets. I began baking at age seven, producing with my cousin, Denis, a mile high cake with sea foam frosting and a chocolate drizzle. I recall that our families were so impressed that I was thereafter declared my mother’s dessert chef for her parties. When Julia Childs began her television series, my mother christened me, “The French Chef,” because I managed with aplomb to dirty every dish in the kitchen whenever I cooked.

By my early twenties, I had already lived abroad, so was quite attuned to European cuisine. Alice Medrich opened Cocolat in Berkeley’s Gourmet Ghetto, and it was not long before her amazing French tortes found their way into Bon Appétit magazine. I determined to master the art of the perfect genoise and the slick ganache. I cannot recall one flop. None was difficult—just time consuming and a bit expensive, given our limited budget while my older daughter, Anna’s daddy was in law school. Good chocolate, fresh nuts, and unsalted butter were luxuries on this teacher’s salary.

By my early twenties, I had already lived abroad, so was quite attuned to European cuisine. Alice Medrich opened Cocolat in Berkeley’s Gourmet Ghetto, and it was not long before her amazing French tortes found their way into Bon Appétit magazine. I determined to master the art of the perfect genoise and the slick ganache. I cannot recall one flop. None was difficult—just time consuming and a bit expensive, given our limited budget while my older daughter, Anna’s daddy was in law school. Good chocolate, fresh nuts, and unsalted butter were luxuries on this teacher’s salary. I have also been on a mission to teach my son, Kevin, the fine art of cooking, and as he finished dinner, I told him he was going to learn to make Clafoutis d’Abricot—a French dessert that is a bit of a cross between a pudding and a cake. The typical clafoutis is made of fresh cherries, but as my daughter, Anna, best said it: we like to eat the cherries as is and we have a tree filled with apricots. The batter is nothing more than a basic pancake or crepe batter. We first whipped that up in the food processor, with Kevin doing the measuring. As soon as we left the batter to rest, we began to prepare the apricots. Because the apricots are fully organic—no sprays of any sort—they only needed a quick rinse. Into the 9-inch pan they went, along with a bit of sugar and a pat of butter. We brought the pan to a quick simmer and pulled it off the heat. Kevin poured the batter on top and in it went into the oven.

Less than fifteen minutes later, we pulled out this glorious soufflé-like dish. I served up a portion, graced it with a scoop of vanilla bean ice cream, and dusted it with confectioner’s sugar. Not too sweet, clafoutis is a perfect light dessert—one that brings back memories of the French countryside and of sunny afternoons. Here is our recipe for Clafoutis d’Abricot, which you can enjoy with any fresh fruit you have on hand or in garden.

Serves 4

½ cup all purpose flour

Pinch of salt

2 large eggs

¼ cup granulated white sugar

¾ cup milk

½ teaspoon pure vanilla extract

¾ - 1 pound fresh sweet apricots

1 tablespoon unsalted butter

Preheat the oven to 425 degrees F and place the rack in the center of the oven. Wash the apricots, slice in half, and remove pits.

Preheat the oven to 425 degrees F and place the rack in the center of the oven. Wash the apricots, slice in half, and remove pits.In your food processor or blender place the flour, salt, eggs, ¼ c. sugar, milk, and vanilla extract. Process for about 45 - 60 seconds, scraping down the sides of the bowl as needed. Once the batter is completely smooth, let it rest while you prepare the fruit.

In a large 9-inch heavy nonstick ovenproof skillet melt the butter over medium heat making sure the melted butter coats the bottom and sides of the pan. When the butter is bubbling, add the pitted apricots, skin side up. Add just enough apricots to cover the bottom of the pan. Sprinkle with the remaining 2 T. of granulated sugar. Cook until the apricots have softened a bit and the mixture has turned into a syrup (1 - 2 minutes). Pour the batter over the apricots and bake for about 15 minutes or until the clafoutis is puffed, set, and golden brown around the edges. Do not open the oven door until the end of the baking time or it may collapse. Serve immediately with a dusting of confectioner’s sugar and vanilla ice cream or softly whipped cream. Bon appétit!

Sunday, June 20, 2010

Commencement: The End of One Journey, the Beginning of the Next

Each educational endeavor we pursue has beginnings and endings. A student matriculates when s/he begins the course of study. When an individual completes that course of study from a university setting, one does not graduate. Instead, we proclaim the rite of passage unique to higher education, "Commencement." I have always loved this term. Commencement is a brilliant amalgam of the past and the future bound in a common moment.

Each educational endeavor we pursue has beginnings and endings. A student matriculates when s/he begins the course of study. When an individual completes that course of study from a university setting, one does not graduate. Instead, we proclaim the rite of passage unique to higher education, "Commencement." I have always loved this term. Commencement is a brilliant amalgam of the past and the future bound in a common moment.

Although I no longer serve as a professor at my beloved former institution, Pepperdine University, I have had the privilege of continuing the journey toward Commencement with some of my doctoral students whose dissertations I chaired far before I left for my present institution, Loyola Marymount University. The role of a dissertation chairperson is perhaps as unique as the term "commencement" is to higher education. It is reserved exclusively for those of the professorate who oversee the work of doctoral level students. It is a sacred trust. It requires years of commitment from the Chair, or "Faculty Advisor," as well as from the candidate. The journey can result in a bond between the two that is forged for a lifetime.

The path of the dissertation is to a great degree a lonely one. A candidate completes the prescribed course of study for the doctoral degree and is then left in the hands of his/her Chair. To varying degrees, universities have support structures in the form of seminars or study groups to help a candidate through the dissertation, but principally it is the task of the Chair to serve as Virgil--the soothing voice of reason--to Dante--the individual on the journey.

The path does wend its way through the Inferno, through Purgatorio, and finally to Paradiso.

The path of the dissertation is to a great degree a lonely one. A candidate completes the prescribed course of study for the doctoral degree and is then left in the hands of his/her Chair. To varying degrees, universities have support structures in the form of seminars or study groups to help a candidate through the dissertation, but principally it is the task of the Chair to serve as Virgil--the soothing voice of reason--to Dante--the individual on the journey.

The path does wend its way through the Inferno, through Purgatorio, and finally to Paradiso.

I often have said to my doctoral students, “In the midst of your pursuit of the doctorate, life happens.” It is life happening that can derail doctoral students from completing the dissertation. In the midst of my own dissertation, my mother was diagnosed with terminal cancer. I needed to care for her, I needed to continue to raise my then-only child, Anna, and I needed to run a school district. Clearly, each of these monumental challenges could have served as a reason to set aside the dissertation--to become one of the dreaded "ABD's" of the planet: a candidate who completes "All but Dissertation." Instead, I did what I counsel each of my students: use the challenge—the defining moment—to move you toward, rather than away from, commencement.

I must stress that the moment-by-moment decision to complete the dissertation is not without its perils. It is perhaps why I frequently hear commencement speakers or Deans or Presidents of Universities praise the family and friends. I have seen marriages end, as did my own when I undertook doctoral studies. Some of my students have faced the death of a loved one and challenges to their own health. On the other hand, some students have added marriage or the birth of their own children to the doctoral plate. Every imaginable life passage becomes a part of the tapestry in the pursuit of the doctorate. Some of these events are tragic; other joyous. But each one returns the candidate to the question of, "Will I complete the dissertation?" Frequently, the late-night conversations I have with my dissertation students are less about data analysis and more about our purpose on this planet. I have alternately been big sister, mother, coach, mentor, and psychiatrist, depending on the need and the moment. In the midst of doctoral education, life happens.

On the occasion of this particular Commencement, the Graduate School of Education and Psychology, I had the opportunity to participate in the rite of passage of several of my former doctoral students. For me, their appreciation of my small role in their journey is exceeded only by the privilege I have of finally seeing them in the greater context of their lives--with their spouses, their children, their parents, and their friends.

I tip a toast your way, Dr. Donna Lewis and Dr. Carolyn Miller, for permitting me to serve not only as your professor, but also as the guide on the dissertation journey. I tip a toast also toward my many other doctoral students from years past, who did complete the dissertation and with whom I have celebrated. Each commencement is a reminder of those occasions of joy and of great accomplishment. In the midst of doctoral education, life happened. Let the new journey commence.

I tip a toast your way, Dr. Donna Lewis and Dr. Carolyn Miller, for permitting me to serve not only as your professor, but also as the guide on the dissertation journey. I tip a toast also toward my many other doctoral students from years past, who did complete the dissertation and with whom I have celebrated. Each commencement is a reminder of those occasions of joy and of great accomplishment. In the midst of doctoral education, life happened. Let the new journey commence.Sunday, May 24, 2009

Reconfiguring the Common into the Uncommon

Caitlin is my second child (and my last) to participate in the Malibu High School Seventh Grade Renaissance Project—one that has historically served as a significant and anticipated rite of passage for all children. I must confess that I did experience much of the angst about which Mr. Gene Bream spoke with my first child’s experience, for prior to that project, Kevin never viewed himself as an artist in any manner, and would frequently enlist his little sister’s support with many of the creative projects that his middle school teachers required. Yet that project served as the catalyst to help Kevin view himself as creative with the visual arts. In the two years since the Renaissance Project, he has demonstrated in countless projects his own innovative and authentic means of expression.

Caitlin is my second child (and my last) to participate in the Malibu High School Seventh Grade Renaissance Project—one that has historically served as a significant and anticipated rite of passage for all children. I must confess that I did experience much of the angst about which Mr. Gene Bream spoke with my first child’s experience, for prior to that project, Kevin never viewed himself as an artist in any manner, and would frequently enlist his little sister’s support with many of the creative projects that his middle school teachers required. Yet that project served as the catalyst to help Kevin view himself as creative with the visual arts. In the two years since the Renaissance Project, he has demonstrated in countless projects his own innovative and authentic means of expression.Following Kevin’s completion of a highly successful project—one that his teacher requested to share with the next year’s class—I carefully tucked away all of the art supplies and paper in a bag marked, “Seventh Grade Bream Project.” This spring I took out the bag and handed it to Caitlin when she came home with her detailed instructions for the project. As Caitlin is highly organized and independent in her learning, I recognized that I would have to prod less to make sure she was staying on target with her project. I did know that any of us is subject to procrastination, however, and wanted to make sure Caitlin had everything she needed to be successful.

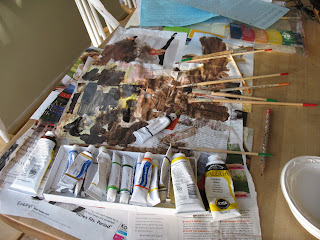

Once our kitchen table became transformed into a full-time artist’s studio, I moved meals to the dining room. Caitlin had full run of the table, which was resplendent with newspapers, small plastic plates that served as her palettes, a large water glass, tubes of acrylic paints, and a dozen or more brushes. I must confess I enjoyed watching her project unfold from pristine, white canvas to washed canvas to one that expressed in its own unique manner the profound, absurdity of Magritte’s The Gradation of Fire. When she completed her work only several nights ago to much celebration, I found myself quite perplexed as to what to do with the beautiful confusion that now graced the table. The process had been as remarkable to watch as the product was to behold, and I reflected on her challenges and successes of the many weeks of work.

“I cannot get the colors to blend properly, Mom!”

“I cannot get the colors to blend properly, Mom!”“Don’t the flames look great?”

“The paint keeps dripping. I am so frustrated.”

“ I love how everything seems to be on fire.”

“I’ve run out of burnt umber and I need it now.”

I hadn’t the heart to change anything, and so, as I gazed at Caitlin with signed painting in hand and the table-studio, I did nothing but stack the palettes of dried paint and organize the brushes. As Caitlin began completing the writing portions of the assignment, she asked me one day, “Mom, why did Mr. Bream have us do this project?” To address her teacher’s writing prompt, she had already come up with several ideas on her own, and as I looked at her, and then toward the art supplies, and finally back at her once again, I offered, “Perhaps it is because art is reconfiguring the common into the uncommon.”

Reconfiguring the common into the uncommon. Inspiration struck. I asked Caitlin if she had any plans to use some of the plates, the stained paper, the damaged paint brushes, or the empty tubes of color. Would she mind terribly if I made a collage from her discarded supplies? I explained to her that I intended to take those common things and create something new and different.

As I launched into the design of the collage, another thought came to mind. Was this not another of Mr. Bream’s reasons for the project—so that our children might serve as muses to us all? With all of the contagions on the planet, this was one of the best of viruses any of us could hope to catch.

Elizabeth C. Reilly is most importantly Caitlin Reilly’s mother, but also a former high school English teacher who now serves as Professor of Educational Leadership at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles.

Labels: http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_dadXz1jrK_c/ShoeqyQxJuI/AAAAAAAAAUM/XZEuKtXdGwE/s320/IMG_0897.JPG

Saturday, March 14, 2009

Down and Out in Malibu

Saturday morning. Ostensibly the only day I can sleep in. I had, however, volunteered for Sherpa duty for my son and his fellow athletes and had agreed to chauffeur them to the bus at Malibu High School by 6:45 a.m. The teenagers were sprinkled hither and yon along our 27 miles of beach, and so by necessity I was up early—far too early for my tastes. Making the long, dark drive down the empty Pacific Coast Highway, I arrived at Ralph’s Market just a bit after 6 a.m. to grab some coffee. Starbuck's was open, but I had been mourning the sale of Diedrich's Coffee a year back and refused on principle to set foot in yet-another-Starbucks-in-Malibu.

Saturday morning. Ostensibly the only day I can sleep in. I had, however, volunteered for Sherpa duty for my son and his fellow athletes and had agreed to chauffeur them to the bus at Malibu High School by 6:45 a.m. The teenagers were sprinkled hither and yon along our 27 miles of beach, and so by necessity I was up early—far too early for my tastes. Making the long, dark drive down the empty Pacific Coast Highway, I arrived at Ralph’s Market just a bit after 6 a.m. to grab some coffee. Starbuck's was open, but I had been mourning the sale of Diedrich's Coffee a year back and refused on principle to set foot in yet-another-Starbucks-in-Malibu.I vaguely recalled the store was not opened 24 hours a day any longer because of the economic situation, but I was not certain. Large stacks of firewood and cases of water surrounded the entrance to the store. I noted a man loading bundles of the firewood into the rear of a new, pearl-colored Mercedes Benz.

Great, the store must be open, I concluded.

As I approached the front door, I bumped into the glass. I could see employees, but as I knocked, thinking perhaps the door was stuck, no one inside responded to me.

The man with the purloined wood quipped, “Well, I guess I just got free firewood.”

As if that wasn’t the plan all along, I thought. He jumped into the backseat of the shiny car and the driver sped off. A full-blown heist in Malibu.

I went to the other door to let the employees know that someone was walking off with their merchandise. The produce man stacked apples inside. I knocked. I called to him. He paid no attention to me.

After collecting the athletes and dropping them off at their high school, I returned to Ralph’s, which was then opened. I looked around for the manager, who usually hovers around the check-out stands. No manager. I concluded my shopping, winding my way through the stockers and their pallets of soda and chips, and went to check out.

“You know,” I reported to the clerk,” I was here around 6 a.m., but you were closed. Some guy in a new Mercedes Benz was walking off with your firewood, and I tried to notify the employees, but no one inside would even so much as look at me.”

“You don’t say,” she replied, less amazed that her colleagues had done nothing and more amazed with my tale.

“Funny thing,” the customer behind me remarked. “There’s a guy in a new Mercedes Benz selling firewood out on the Pacific Coast Highway this morning.”

We all laughed uproariously.

What is not uproariously funny, I noted as I drove back home, is the ghost town appearance of the Pacific Coast Highway these days. My twenty-seven miles of white, sandy beach are littered with shuttered businesses. Pet Headquarters, the former haunt of the rich and famous for chi-chi cats and dogs, doggie designer handbags, and biscotti is gone. It was one of my children’s favorite places, but one where “if you had to ask the price, you couldn’t afford it.” Our rule was, “You can look and pet the pooches, but the moment you ask to purchase one, your mother disappears down the highway with you in tow.” One time I asked how much they wanted for a cat that my son was petting: a cool, five thousand dollars.

“Cats are free agents,” I muttered. “Who on earth would pay for a cat?”

Numerous realty offices have closed. Restaurants—only having opened in the last year—are gone not with a bang but a whimper. On a recent weeknight, a colleague and I caught the late show at our tiny movie theatre. I inquired as to the many businesses closed around us and one young woman said the plan was to replace them with designer shops.

I burst into laughter. “Are you kidding me? Who can afford Juicy Couture and Ralph Lauren these days, if ever? And more shops are coming?” I am not holding my breath.

It gets worse, though. On the online list serve for Malibu High School parents, recent postings included one mother’s request for old books so that she could sell them to make ends meet. Another was looking for part-time housekeeping to pay her bills. Could this be the bastion of double-wides that only a year back sold for a minimum of a cool million? When the track and field coach offered to order sports bags for around $30 per athlete, a parent offered to buy an additional bag for a student who could not afford it. But in a place where appearances can mean everything and reality little, would any parent actually step forward and say he could not afford this for his child?

The ugly truth is that this global economic crisis has infiltrated into the haven of the rich and famous. As surely as the fog slips over the ocean and up the canyons at night, the financial downturn has settled over us as a death shroud. I’ve heard tell of those in town who lost millions to Bernie Madoff’s make off. And that was after everyone’s 401K’s tanked. My realtor friend told me that the number of foreclosures in town is record-breaking. You can count more For Sale signs than surfboards these days. She, herself, hasn’t sold a home in a year. I’ve come to ask my friends how their “AK 47’s” are doing, which they find hopelessly amusing, given that I hang in war zones with bodyguards who tote them with as much grace as the actresses with their Louis Vuitton handbags at Nobu.

And therein lay the stark and odd contrasts. Nobu still has a crowd. The new restaurant, Charlie's, which just opened across from the Malibu Pier, was packed last Thursday night. Each dessert is eight dollars and most tables were ordering them. Just yesterday, Rosenthal Winery’s Tasting Room by Beau Rivage Restaurant was overflowing with tasters imbibing—and it’s not free, either. Someone, somewhere is still flush. But who? Or, are they really?

What I have told my children is this: In a world such as we are in at present, there is a circle-the-wagons mentality that can take hold. It consists of two aspects: first, we pretend that everything is just fine and belly up to the bar, prices be damned. Second, we hold the sneaking suspicion that it is awful out there beyond our little enclave—and perhaps even within our own walled city—but we are going to hoard and refuse to share. It’s not unlike what you faced when you were five and the kid in your kindergarten class would not give up the stuffed dog you wanted to hold.

There is, however, another way to view this time, and it really is a choice. A couple of nights ago on The Colbert Report, Princeton philosophy professor Peter Singer was presenting his new book, The Life You Can Save: Acting Now to End World Poverty. In Colbert’s perfectly cheeky manner, he questioned why any of the remaining wealthy would want to share, including himself in his expensive alligator shoes. And whatever would the poor do with his Audi? Dr. Singer asked this question:

“If you were walking by the lake and you saw a child drowning, would you risk your alligator shoes and jump in and save her or keep going?"

Singer challenges us to recognize that drowning children are all around us. I would add that they are not even that far beyond our doorstep, if we only choose to pay attention. Furthermore, he impels us to face the moral imperative of doing something about it.

Singer challenges us to recognize that drowning children are all around us. I would add that they are not even that far beyond our doorstep, if we only choose to pay attention. Furthermore, he impels us to face the moral imperative of doing something about it.I go a bit beyond Dr. Singer, though. I believe that we are in the midst of a defining moment as civil society. It is not only that people are starving, but that they are starving for a voice and a place that matters. As I reflect on the tens of thousands of lawyers in Pakistan who are taking to the streets this very day who are hungry for a just society; the millions of Afghan children who are hungry for an education; and the people in my own state who are hungry for meaningful work, I recognize I cannot afford to wring my hands and worry only about myself.

Robert Frost reminds us that, “The best way out is always through.” I would suggest that the only way out is by taking the hands of others and then proceeding through. Take a moment today to decide where you can help someone who is starving—for a meal, for a voice, for a purpose. Now, leave the wagon and take action. My hunch is you will find your own belly, heart, and mind full, as well.

Tuesday, February 03, 2009

Hafa Adai: Over One-half a World Away

"I had to laugh when you gave me the address for your hotel here on Saipan. We don't use addresses! When you land, you'll understand everything."

It dawned on me that what the locals call their "tiny speck in the ocean" where I would spend the next two weeks would be easily navigable. When I have told people I was coming to Saipan, the reactions have been somewhat similar.

"Spain should not be so cold this time of year."

"You'll love the sushi in Japan."

"I do not know anyone who goes to Saigon."

Saipan. The Commonwealth of the United States of America. That means it is ours. It is us. Saipan became affiliated with the USA following World War II, when we took it from the Japanese, who took it from the Germans, who in turn took it from Spain, who took it from the indigeneous peoples--the Chamorro and Carolinians, which still do live here. Saipan, which is part of a necklace of islands called the Mariana Islands, is in the area of the Pacific Ocean we call Micronesia. It is barely 35 minutes from Guam and has two, other close neighbors, Tinian and Rota--two additional tinier specks in the ocean. Off the coast of azure water rest at least three US aircraft carriers that stand poised to protect Saipan and her sister islands, should the need arise. Unlike a lot of the places I spend time, I do not see soldiers wielding AK-47s. Its ethos is a great deal similar to Hawaii in terms of weather, food, and sensibility.

To get to Saipan is a several step endeavor even from California. You can fly to Narita International in Tokyo, drop down to Guam, and then hop down to Saipan or you can fly through Honolulu, and then follow the route through Guam and onto Saipan. What I do know is that it results in about 6,500 frequent flier miles each way, a cross over the International Date Line, and 18 time zones beyond California.

Tuesday, November 18, 2008

Reunion Across Sixteen Time Zones

Daily I experience the remarkably few degrees of separation between others and me in this very flat world. Back in April in Boston, I met William Valentino, a Vice President with Bayer China, whose daughter worked in Kabul, Afghanistan, from where I had only returned days before. Who hangs out in war zones, let alone works in them? Yet there it was: Bill’s daughter and me in the same land-locked country in South Asia, donning hijab, helping to rebuild a nation in crisis. Bill, quite the force of nature with his vast array of social programs which he oversees in China, agreed to host my doctoral students in Beijing in May, where it just so happened was my next destination. The students were utterly taken with his work and his lifelong commitment to the nation. HIV-AIDS, rural development, education—little escapes Bayer’s touch.

Within hours of the tragic earthquake during our visit, Bayer was providing relief efforts to the victims. My tour guide in China, Lili Li, who had been in touch with Bill at my request before our arrival, asked if he was from Szechuan province. I laughed uproariously as I explained to her that Bill was not Asian, but rather a Caucasian boy from New Jersey. His Mandarin was that good, as was his navigation of Chinese restaurant protocol, where we enjoyed the choicest slices of Peking duck, thanks to his gracious manners. Following that visit, he and I learned that we were both invited to present at the Asian Forum on Corporate Social Responsibility in Singapore in November. A reunion was clearly in the making.

Singapore via Switzerland

Another reunion was also on the horizon, however. In flight between Kuala Lumpur and Bangalore in April 2006, I met Peter Andrist, Vice President of Business Development for GateGourmet, that multinational corporation that provides food for many of the airports throughout the world. (For my first story about Peter, see my blog titled Culture 101 from Tuesday, April 18, 2006.) A Swiss-born citizen whose company was based in Seattle, Washington and who lived in Bangkok, Peter Andrist is responsible for acquisitions for his company throughout Asia.

Peter represents to me the epitome of a leader for the 21st century—an individual who can flow with alacrity and confidence in and out of cultures. Peter appreciates the differences between and amongst the many nations in which he finds himself and yet knows how to build bridges with people. Little daunts him and nearly everything brings a twinkle to his eyes. These past two and one-half years we have stayed in touch, although I had not had the opportunity to meet with him whilst he lived in Bangkok and to conduct a formal interview about leadership.

Peter represents to me the epitome of a leader for the 21st century—an individual who can flow with alacrity and confidence in and out of cultures. Peter appreciates the differences between and amongst the many nations in which he finds himself and yet knows how to build bridges with people. Little daunts him and nearly everything brings a twinkle to his eyes. These past two and one-half years we have stayed in touch, although I had not had the opportunity to meet with him whilst he lived in Bangkok and to conduct a formal interview about leadership. Around May of this year, Peter mentioned to me that he would be moving to Singapore, where coincidentally I would find myself this November, and so it was that we made a plan to meet once again and talk about leadership in a global society. In one of Singapore’s typical torrential deluges, Peter greeted me with his intense blue eyes and wide smile, and we headed to Indochine Waterfront, a marvelous restaurant featuring cuisine from several Asian nations, situated on the Singapore River in the old colonial civic district. Glasses of Sauvignon Blanc in hand, we toasted our reunion and proceeded to talk about foreign policy, Asian cuisine, corporate social responsibility, and the many things we had been doing since the time last we had met at 36,000 feet over Malaysia Airlines’ famous satay.

Over intensely spicy Thai seafood Tom Yam soup and Vit Quay Gion Ton Kin—French duck fillets grilled with herbs and spices—I reminded Peter that his love of food reflected his childhood desire to be a chef. He laughed that I had remembered this very first story he had shared with me, but added to it when I asked how it was that he embraced a world far beyond the tiny town in Switzerland in which he had grown up.

“Do not laugh, Elizabeth, but Switzerland has a Navy. Yes, I know we are land-locked, but it is so, as amusing as that is. I wanted not only to be a chef, but one aboard a large ship,” Peter added.

At age fifteen, he set off for Genoa, Italy where he caught a freighter to Lebanon.

Reflecting at the prospect of my young son, who just turned fourteen, taking off around the world on his own, I queried if this distressed his mother. Peter replied that he did not have the typical teenage vices—no drugs, no criminal intent—and so as the eldest child, he had some amount of leverage to chart his own course.

“This was just before the war in 1971 and so Beirut was simply lovely. Now, of course, it is utterly destroyed. The ship had perhaps only seven small cabins for passengers. I made friends with a Catholic priest on board. When we disembarked, the priest greeted his cargo—a new Mercedes Benz automobile filled with arms.”

“Peter,” I probed, “You know that priests take vows of poverty. What on earth was a priest doing with an expensive German car and a cache of weapons?”

“Recall I was a child,” he reminded me. “Had I been older, I would have asked such questions, but what did I know?”

Following this first taste of the world, Peter never lost his love of travel. Speaking a raft of languages fluently, he has lived in many nations and has a deep love of the varying colors of the many cultures he encounters. Ankor Wat in Cambodia? Several times. Viet Nam. The same. Egypt. Please. He lived there. I found it quite surprising, then, to learn that I had somehow managed to find myself earlier this year in a country in which Peter had never been: Afghanistan. He was utterly captivated with my stories of the challenges the Afghan people face each day: security, education, meaningful work for their hands, a roof over their heads.

“When I met the Chancellor of Kabul Medical University, he said to my student, Mirwais, and me, ‘I am going to tell you about my school, I am going to answer your questions about leadership, and at the end, I am going to ask for your help.’ Peter, that month in Afghanistan transformed me. There is much to do, much to do.”

Peter and I agreed to continue the conversation and to imagine what we might do to continue our work in the world.