Reconfiguring the Common into the Uncommon

Caitlin is my second child (and my last) to participate in the Malibu High School Seventh Grade Renaissance Project—one that has historically served as a significant and anticipated rite of passage for all children. I must confess that I did experience much of the angst about which Mr. Gene Bream spoke with my first child’s experience, for prior to that project, Kevin never viewed himself as an artist in any manner, and would frequently enlist his little sister’s support with many of the creative projects that his middle school teachers required. Yet that project served as the catalyst to help Kevin view himself as creative with the visual arts. In the two years since the Renaissance Project, he has demonstrated in countless projects his own innovative and authentic means of expression.

Caitlin is my second child (and my last) to participate in the Malibu High School Seventh Grade Renaissance Project—one that has historically served as a significant and anticipated rite of passage for all children. I must confess that I did experience much of the angst about which Mr. Gene Bream spoke with my first child’s experience, for prior to that project, Kevin never viewed himself as an artist in any manner, and would frequently enlist his little sister’s support with many of the creative projects that his middle school teachers required. Yet that project served as the catalyst to help Kevin view himself as creative with the visual arts. In the two years since the Renaissance Project, he has demonstrated in countless projects his own innovative and authentic means of expression.Following Kevin’s completion of a highly successful project—one that his teacher requested to share with the next year’s class—I carefully tucked away all of the art supplies and paper in a bag marked, “Seventh Grade Bream Project.” This spring I took out the bag and handed it to Caitlin when she came home with her detailed instructions for the project. As Caitlin is highly organized and independent in her learning, I recognized that I would have to prod less to make sure she was staying on target with her project. I did know that any of us is subject to procrastination, however, and wanted to make sure Caitlin had everything she needed to be successful.

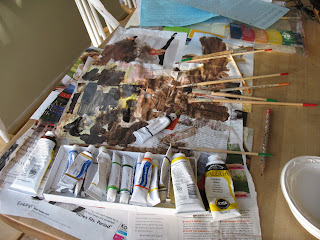

Once our kitchen table became transformed into a full-time artist’s studio, I moved meals to the dining room. Caitlin had full run of the table, which was resplendent with newspapers, small plastic plates that served as her palettes, a large water glass, tubes of acrylic paints, and a dozen or more brushes. I must confess I enjoyed watching her project unfold from pristine, white canvas to washed canvas to one that expressed in its own unique manner the profound, absurdity of Magritte’s The Gradation of Fire. When she completed her work only several nights ago to much celebration, I found myself quite perplexed as to what to do with the beautiful confusion that now graced the table. The process had been as remarkable to watch as the product was to behold, and I reflected on her challenges and successes of the many weeks of work.

“I cannot get the colors to blend properly, Mom!”

“I cannot get the colors to blend properly, Mom!”“Don’t the flames look great?”

“The paint keeps dripping. I am so frustrated.”

“ I love how everything seems to be on fire.”

“I’ve run out of burnt umber and I need it now.”

I hadn’t the heart to change anything, and so, as I gazed at Caitlin with signed painting in hand and the table-studio, I did nothing but stack the palettes of dried paint and organize the brushes. As Caitlin began completing the writing portions of the assignment, she asked me one day, “Mom, why did Mr. Bream have us do this project?” To address her teacher’s writing prompt, she had already come up with several ideas on her own, and as I looked at her, and then toward the art supplies, and finally back at her once again, I offered, “Perhaps it is because art is reconfiguring the common into the uncommon.”

Reconfiguring the common into the uncommon. Inspiration struck. I asked Caitlin if she had any plans to use some of the plates, the stained paper, the damaged paint brushes, or the empty tubes of color. Would she mind terribly if I made a collage from her discarded supplies? I explained to her that I intended to take those common things and create something new and different.

As I launched into the design of the collage, another thought came to mind. Was this not another of Mr. Bream’s reasons for the project—so that our children might serve as muses to us all? With all of the contagions on the planet, this was one of the best of viruses any of us could hope to catch.

Elizabeth C. Reilly is most importantly Caitlin Reilly’s mother, but also a former high school English teacher who now serves as Professor of Educational Leadership at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles.

Labels: http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_dadXz1jrK_c/ShoeqyQxJuI/AAAAAAAAAUM/XZEuKtXdGwE/s320/IMG_0897.JPG